Slowly Going Broke!

My new bosses asked me to pay a visit to the farm about a week after they’d hired me. My task was to count a mob of cattle that hadn’t been mustered when the stock take occurred. It was a typical Southland winter day when I arrived, a biting sou’wester was blowing, and as I approached the Cairn Peak boundary for the first time, I took in the run-down fences and the overgrazed paddocks.

I drove on to the cattle yards where a mob of breeding cows were milling around in a sea of mud. They were skinny, of an indefinable breed, and totally spooked by their hunger, their need for shelter, and the horizontal sleeting rain. I opened the gate and tallied them as they galloped past me, heading to the shelter of the hills. What on earth had I let myself in for?!

Cairn Peak was a hill country run comprising a series of ridges rising to 2,100 feet, with most of these bisected by scrubby gullies of bracken, manuka, and native Beech. The property was purchased in July 1964. The three new owners had mortgaged their houses and paid £53,183 for 5,176 acres of land, 191 head of beef cattle, 2,325 sheep, a dairy cow, one pig, and two hacks.

Cairn Peak homestead from the air 1964. The surrounds are unappealing and underdeveloped.

At the time of the sale, the vendors had split up a 12,000-acre holding, kept 6,800 acres of the superior country to farm themselves and sold the balance to my new employers. This smaller block was named Cairn Peak after the highest peak on the property and, up to this stage, had never been farmed as a standalone operation. The homestead and other improvements had been recently built to make the sale viable, and the livestock had been well picked over before being assigned to the purchasers.

Eight weeks earlier, in May 1964, Rosie and I were married. We’d successfully applied for a farm management position and took up residence a week after the incident above. The weather had cleared, and very early on the first working day of my new job I saddled a horse and set off to explore my new domain.

It was a beautiful morning when I set out and it wasn’t long before three red deer broke cover and scampered off into the distance. My spirits rose immediately.

I concluded after my ride around the property that Cairn Peak was a mixed bag of good and bad. On the positive side, the wool shed, and the sheep and cattle yards were satisfactory, and the homestead was relatively new and comfortable. In addition, two thirds of the hill country was covered in clean tussock and would provide good summer grazing. On the down side the fences were dilapidated and the paddocks in need of drainage. Much of the hill country was scrubby and gorse infested, and there just wasn’t enough cultivated pasture to support the number of sheep and cattle the vendors claimed the property could carry.

The next few weeks were chaotic. I convinced the owners of the importance of purchasing more stock feed to get us through until spring. I drafted the breeding ewes into early, medium and late lambers to help conserve feed and called a meeting with the three owners to present my interim budget. At the end of the meeting, I was heartened by their acceptance of my recommendations but less encouraged by the uneasiness etched on their faces as they poured over the budgets.

The new owners were business people and had been wooed by the size of the property and the attractive tax write-offs available. However, I hadn’t been in the district long before pub talk surfaced that “Cairn Peak had been purchased by a bunch of townies who had paid too much, and were slowly going broke”. There may have been some truth in this, but I was highly motivated to prove them wrong.

The original property, I was beginning to learn, had a checkered history. It was endowment land, owned for more than a century by the Bluff Harbour Board. There was plenty of evidence on file, of the struggle some of its previous lessees went through, to make ends meet.

During the depression years the 12,000 acre run had been leased by a Peter Hogg who in an impassioned letter to the Harbour Board dated 24th February 1937 pleaded for rent remission and assistance to build a homestead on the property. He wrote “my wife and three children are living in tents at the present time and have been for the last four years. Their ages range from 12 to 16 so they have literally been reared in these tents.” He went on to say, “if you can’t support me, bring Mr Langstone (the inspector from Wellington) to see my habitation when he is next in Southland and see if he is proud of his part in our plight.”

So ever the risk taker, and in full knowledge we were over stocked and under capitalised, I called a meeting of the owners and put a proposition to them. I proposed I buy a 25% share of the enterprise for £10,000, to be paid for, (i) by cash from the sale of my brand new Vauxhall Velox, and (ii) by accepting a significant salary sacrifice for the ensuing years until the debt was repaid. They didn’t demur so within six months of our employment, we had became one of four equal owners.

This meant that Rosie and I had chosen to live “on the smell of an oil rag” for the foreseeable future. I was confident that my knowledge of the workings of the Lands Department (I had previously worked as a field officer for them,) would make us prime candidates for a marginal lands loan. Sadly, I couldn’t have been more wrong!

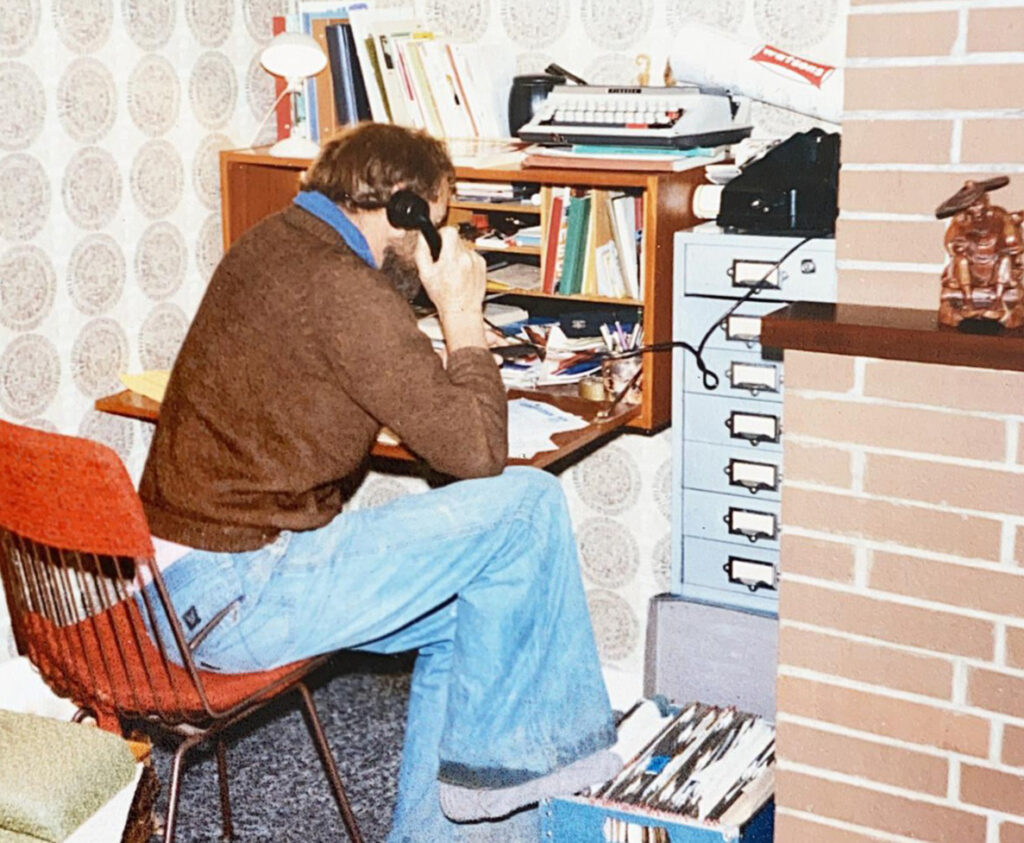

A day in the office.

Marginal Lands loans, were designed to assist young farmers into farm ownership. High importance was placed on (i) The worthiness of the applicant,(ii) proof that all other avenues for mortgage finance had been exhausted. (iii) The property was marginal in its nature, and (iv) the provision of a low interest loan would reasonably be expected to result in the applicant becoming a successful farmer.

The Southland Marginal Lands committee paid us a visit, supported our application and submitted their recommendation to the Commissioner in Wellington. The commissioner disagreed with the Southland committee and turned us down on the grounds we were a bad risk financially, and they were not convinced we could service the loan. Rebuttal number one!

Thanks to obtaining 2nd mortgage finance from a private source, to help fund our development program, we managed to remain solvent through another season. Confident of success this second time around, we reapplied for a Marginal Lands loan.

In my submission to the Commissioner of Crown Lands I wrote “We have occupied this property for 25 months now and in that time we have :-

- Erected 6 miles of subdivision fence

- Sod seeded 68 acres of tussock

- Ploughed and grassed 38 acres from native and aerially oversown with grasses and clover, a further 22 acres of sidling within the same block.

- Ploughed a further 48 acres from tussock and 38 acres of badly run-out gorse-infested hill pasture

- Renovated 83 acres of inferior pasture

- Oversown 250 acres of tussock with 10lb of seed and 4cwt of super per acre

- Erected ten major bridges and culverts

- Bulldozed 3 miles of strategic access tracks

- Installed a new homestead water supply

- Caught up on a considerable amount of deferred maintenance on plant and fences.

- In addition:

(i)Average wool weights have risen from 7lb to 9lb.

(ii)Death rate of our sheep has dropped from 8 1/4 % to 6%

(iii) The lambing percentage has risen from 73% to 90%.

Rebuttal number two arrived in a letter from the office of The Minister of Lands Wellington, on 5th December 1966. “The board has now carefully re-examined this case in the light of further information supplied by the management of Cairn Peak Farm Company, but once again has resolved that the application must be declined. The main factor influencing the board in its decision was the very high debt which the property would have to carry if the advance sought was approved. On completion of the planned development program the debt, including the new rental value to be assessed in 1969 would be about £68,000 and members were quite satisfied that despite the high standard of management by Mr Fife, the property could not service the debt.

Not prepared to accept this decision I wrote to our local Member, the Hon Brian Talboys, who forwarded my missive to the minister of Lands, who re- forwarded all the information to the Minister of Agriculture for his comment. The usual merry go round.

On 22nd September 1967 I received a letter from Mr AR Rankin, the Department of Agriculture Field Superintendent in Southland containing the following comments. :- I understand the Minister of Agriculture suggested you obtain comments from me. As I told you when you first approached me, I would offer you no support unless I visited the property, inspected your husbandry of the property and examined your financial situation. Providing I was satisfied that you could succeed, I would be prepared to support your case. I reached the same conclusion as the local Marginal Lands committee namely, that your debt commitment was high but that the skill which you were demonstrating as manager provided sufficient leeway to warrant Marginal Lands finance.

I was particularly pleased, from my own personal point of view, with your efforts as you were demonstrating what could be done on this class of country and providing an example to other landholders in the area. From the National point of view, your efforts were giving impetus to the increased production drive, not only on your property but also by the example you were setting in an area previously not tackled with any enthusiasm. I was indeed sorry to hear that the Board differed, not only with my opinion but with that of the local committee.

Mr Rankin went on to say – the real problem, however, is related to the likely increase in rental due to the reclassification of the property, which is due in 1969. And yes, this pending, exponential increase in our rent was yet another problem we now needed to deal with. We had no option but to tackle the issue through the courts.

At this stage, Rosie and I were worrying about our financial situation and took steps to divest all my personal assets into her name in case Cairn Peak became insolvent. Despite this, they were happy years. We were making steady progress with the farm improvements. We’d gained the respect and support of the Lands Department and the Agricultural Department representatives in the Southland province, and most importantly, I could hold my head high in the Dipton pub. We’d proven to the locals that we did know what we were doing, even if we were slowly going broke!

During these early years, In April 1965, our first daughter Nicola was born. In those days, husbands seldom attended the birth. The matron at the Winton maternity hospital had iron-fisted control and wasn’t having “gormless males” cluttering up the birthing centre while she was in charge. This was despite many of these gormless males being pretty handy at assisting their own breeding stock with difficult births.

The following year in August 1966, our 2nd daughter Joanna was born. I couldn’t take my place with the other nervous dads in the waiting room that day due to a cattle muster held up by the weather. We were waiting on the mountaintops for the clouds below to disperse before we could start the muster. Thankfully, apart from Joanna sporting a bright yellow jaundiced complexion, she and her mum were just fine when I arrived at the hospital later in the day.

Joanna, Graeme and Nicola. Glendhu Bay Wanaka 1968.

Our son Graeme was born in March 1967. We now had three children under three, and Rosie experienced her third delivery once again without me there to support her. I was 300 kilometres away in Central Otago buying Merino wethers at the annual Omarama sheep sales.

Also during this period, one of the partners had lost confidence in our ability to ever be rescued from the treadmill of debt, so he sold his share at cost to his fellow tax accountant, Bill Piercy. Cairn Peak now had three shareholders, with Bill owning a 50% share

Finally, in 1967, three and a half years after the purchase of Cairn Peak, we received the first letter from any government source with good news. Our legal challenge to the classification of our land had been successful, and the Minister of Lands notified us – “Your lease can now be changed to a standard Renewable Lease under the land act 1948, carrying the right to acquire the freehold. The Department is prepared to issue a lease on this basis.”

The effect of this change of heart was significant. There was an exponential rise in the value of our holding which made us eligible to obtain 3rd mortgage finance at an attractive rate from the State Advances corporation. It was almost an anticlimax when the loan was approved in December 1967 and we acquired the freehold right to the property.

We finally had the paperwork to prove that, in the opinion of two separate government departments, we were no longer slowly going broke!

Neighbours

There’s a story among farming people that, on coming to live in a rural community, a new arrival once asked, “what are the neighbors like around here?” The old resident said “what were they like where you came from?” and his rejoinder was “They were great” to which the old resident said “you’ll find them great around here too.”

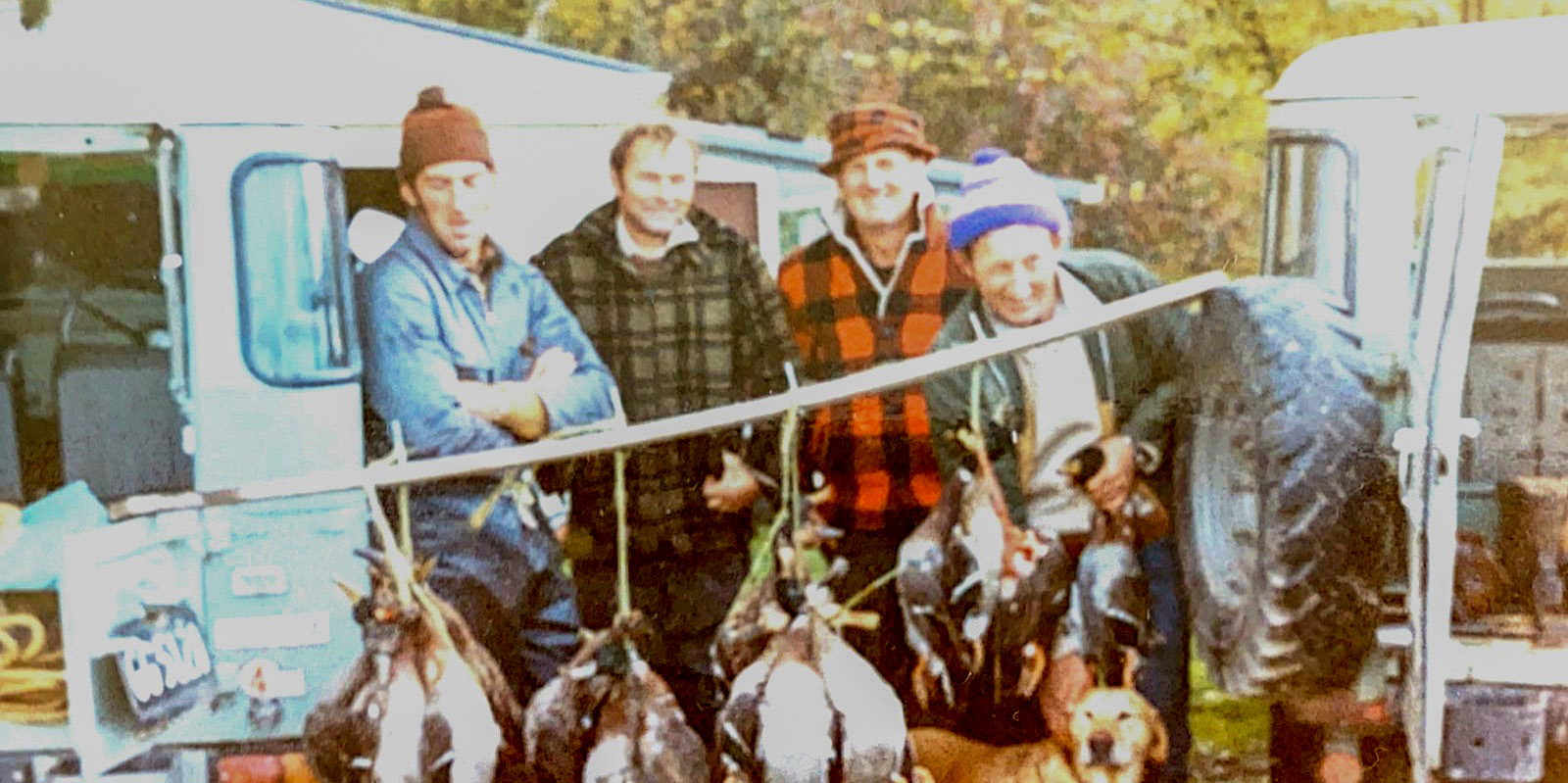

Duck shooters. Rosie’s brother Peter Peterson, Me, Gordon Leith, Jim Love.

In the seventeen years we lived in Southland, we found the neighbours to be great, though some a little quirky. There was Gordon Leith who appeared aloof for a while but once invited to share a spot in our hide at duck shooting season became a firm friend. Always insisting on supplying the whiskey to keep out the cold and even prepared to share a slurp from his glass with the labrador each time he swam back with retrieved ducks in his mouth!

I was having a drink in the Dipton Pub in the summer of our first year and was introduced to an old bloke called Alf who lived on his own. It turned out he owned 800 acres of good country further North along the Taringatura ranges. We’d survived our first winter and were earning grudging respect in the district. Alf asked me how things were going and said diplomatically, “I’ve heard you guys didn’t get much of a bargain when you bought your property”, to which I replied, “We’re doing alright but dealing with an overstocking problem”.

Cattle on the move, stringing back home to Cairn Peak 1965.

Alf nodded wisely, “Yeah, I heard Murray Day (the vendor) had a big celebration when you fellas came along. Tell you what, how many breading cows do you have?” I told him, and he said, “I’ve got far too much tucker on my place, bring them down, and I’ll graze them for you until they’re ready to go out to the bull.”

This was an offer generous beyond belief. I was being offered three months free grazing for all our breeding cows, with no strings attached. He’d taken a shine to me and was happy to be able to help a struggling young farmer. We herded the cattle along the circuitous back country roads to his property and when we brought them back they were in beautiful condition, well primed to survive another winter on the bleak hills of Cairn Peak.

Despite my protestations, Alf wouldn’t dream of accepting payment. Sadly, after all these years, I can’t remember his surname.

I have more anecdotes to share about our colourful neighbours in the next edition of my story.

Ken Fife

6th April 2022

Valediction

This shot was taken in the late 1960s when Denis was manager of Mutti Sheep station in Central West Queensland.

Two weeks ago, on March 24th 2022, Denis Carlisle passed away in Canberra. When I was a young man in NZ, Denis ran the local shearing gang and was the fastest and cleanest shearer ever to grace our shearing shed. I once saw him win a bet by shearing a full fleeced sheep whilst blindfolded in under ninety seconds.

Vale Denis. Gun shearer and lifelong friend.