By the end of the 1970s, things were going well on Cairn Peak. Pinnacle Pine forest, our second forestry syndicate was fully subscribed and we now had 2,000 acres committed to farm forestry. Since taking up residence in 1964, we’d trebled our carrying capacity, tidied up the farm purchased from Bob Mitchell and were now able to fatten most of our livestock prior to sale.

We’d negotiated some lucrative barley malting contracts and were obtaining yields on our fertile flat land in excess of 15 tonnes per ha. Rumours of going broke were long dead and one day, after I’d driven up to the Dipton pub in our new Land Rover, I heard the son of a privileged farming family muttering behind closed fingers to a friend, “here comes the nouveau riche.” How things had changed.

On 7th December 1978 I received a letter from Ministry of Foreign Affairs saying they’d been advised by the Fiji government, that my nomination for the position of Ranch Manager for the Uluisaivou corporation in Fiji had been formerly accepted. Our life was set to change as we prepared to relocate our family for a two year stint in the South Pacific.

The Uluisaivou project was funded by the NZ Government under their bi-lateral aid program and was designed to introduce a cooperative farming venture into a remote native land area in north Viti Levu. Two New Zealanders had been leading the project and I was to replace the Ranch Manager who was returning home.

In the preceding three years, remote villages had been opened up with the building of new roads to replace centuries old walking tracks. Most children in the area now had access to schooling and the sick were more easily transported to hospital. In addition some of the physical infrastructure necessary to support a modern cattle farming enterprise was in place, and 2,000 head of cattle were grazing the hills for the first time.

The scheme involved 120,000 acres of hilly native land and approximately 2,000 people living in 22 widely dispersed villages.

My new role as Ranch Manager was to supervise the continuing land development, as well as the sugar cane farming and cattle ranching activities. The staff consisted of 4 stock-men, 3 gangs of 6 fencers, 2 mechanics, 3 tractor drivers, and a typist-secretary. In addition, there were 3 Agricultural Department employees on site, sponsored by the Fiji government. I was to learn in time that rightly or wrongly, the villagers’ expectations of the ex patriot Ranch Manager’s responsibility went beyond managing the ranch.The Uluisaivou scheme was a big deal to these people and by the time I left I drew far more pleasure from my connections with the villagers, than from achievements we’d made in the cattle ranching enterprise. This was hardly a surprise because it wasn’t long before I realised, the cattle farming venture as it was presently set up was doomed to failure.

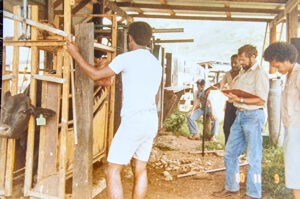

Graeme, checking out cattle in Fiji – a lot different than on the farm at home!

Back in NZ we engaged a manager to run Cairn Peak whilst we were away. Graeme and Joanna were still in primary school so would live with us on site in Fiji during 1979 qnd receive their schooling by correspondence. Nicolla was enrolled in Southland Girls College in Invercargill as there were no boarding facilities at the international school in Suva. In 1980 Joanna joined her sister in boarding school and the two girls became seasoned travelers, the terms of my employment contract stipulated they would be flown to Fiji for all NZ school holidays.

Suva

In January 1979 we set off for Suva armed with our green official passports. These didn’t grant us any diplomatic privileges, (like red ones), but did put us in priority queues with customs and airport officials. This was just as well as I’d been asked by Foreign Affairs department to take my rifle. We’d occasionally be required to provide meat for village ceremonies, and given that local slaughtering practices were inhumane to say the least, on those occasions it was better for me to assume the role of executioner.

I’ve never walked into an airport Customs hall with a hunting rifle before, but production of our green passports smoothed the way and through we went.

We spent our first week getting acclimatised to a hot steamy Suva and were charmed by its 1970s colonial atmosphere. The pace was relaxed and at mid day everything ground to a halt. It was common to see pairs of policemen holding hands as they walked along, dressed in their white uniform sulus (traditional skirts.)

I’m embarrassed to say I had a safari suit made after I’d been convinced by an Indian tailor that this was the preferred dress for self respecting ex patriots. Mine had short pants, short sleeves, and an impressive jacket with wide pockets on the sides. I wore it a couple of times in Suva but it stayed in the closet once we’d taken up residence at Uluisaivou. This was not only because it looked ridiculous, but also because after 6 weeks in the tropics I’d lost so much weight it no longer fitted.

During our week in Suva we had briefing sessions in the NZ High Commission, we spent some “get to know you” time with John Stone, the project’s general manager. We met some Ministry of Agriculture officials, and were supplied with briefing papers containing valuable information on Fijian culture. Included with this material was a small yellow publication containing common Fijian conversational phrases.

In the early 1800s the missionaries when committing spoken Fijian to a written language, introduced a system for certain letters of the English alphabet to represent Fijian sounds. Here are some examples.

c = th as in that. ……. Sucu pronounced suthu

b = mb as in number. …….. Bau pronounced mbau

d = nd as in sand . …….. Nadi pronounced Nandi

g = ng as in ring ……… Vavalagi pronounced Vavalangi

q = ng-g as in finger. …….. Yaqona pronounced yang-gona

I have no idea why they didn’t just spell the words exactly as they were pronounced. Yaqona spelt with a q makes no sense. It would more sensibly be yangona. The illogical missionaries of the day have much to answer for!

I was determined to learn to speak Fijian whilst I was there and made a concerted effort with only moderate success.

Uluisaivou

We were all excited when the General Manager drove us on an introductory one-day visit to our new home. There we were treated to a traditional welcoming ceremony which also served as an official farewell for Rhod my predecessor.

Welcome ceremony for me on the left, and farewell ceremony for Rhod, 3rd from right. There are six village chiefs and three Fiji Ag Dept staff also in this shot.

The largest village in our bailiwick was called Nabalabala (pronounced Nambalambala, those meddling missionaries again!) It was situated at the bottom of a hill near a small river. This was a natural swimming hole popular with the locals and our 3 kids. Half way up the hill and clustered together on a ridge were two houses, plus the company office, and the workshop. This site provided a good view over the valley with the added benefit of exposure to the cooling breezes. The house was unpretentious and comfortable, perfectly adequate for the tropics.

We took up permanent residence 3 days later, and there was a welcoming Meke (celebratory dance) put on for us by our staff that evening. There were plates of fruit and some hot food, and dancing to music provided by transistor radios and guitars. Luckily I’d been warned by the General Manager in Suva what to do when Tevita the Head Stockman came forward and tapped me on the knee (I was sitting down). This was an invitation to dance with him but no, he didn’t fancy me, he was being polite to a newcomer. So Tevita and I boogied away and everyone joined in and a good time was had by all.

Once our possessions were unloaded that first day, Rosie set about turning our house into a home while I went to find the local shop to purchase some white spirits for our lantern. The “shop” was a tiny tin shed at the junction of the main road about 8 kms away.

I drove down the hill in our land cruiser, turned right at Nabalabala and before long came upon a straight backed old man walking along the road. He had bare feet and grizzled hair, he was wearing his best sulu and he walked with a stick. We’d been told there were no private vehicles in our territory and it was polite to offer a ride to people on the road. So I stopped, wound down the window:

Me – “ko via vodo?” Would you like a ride?

Man – “io, vinaka vaka levu” Yes thanks very much.

Me – “ko ca lako i vei?” Where are you going?

Man – “au sa lako ki na bure oya” I’m going to the house over there,” pointing to a small thatched native house in the distance

Me – “OK, koce na yacamu?” OK, What is your name?

Man – “mi yacagu es Ilisoni, ko ce su yacamu?” My name is Ilisoni, what’s your name?

Me – “mi yacaqu es Ken” My name is Ken.

He looked at me, nodded gravely, then couldn’t contain himself, and he laughed and laughed. Finally, he said, “Actually, you’ll find most of us speak pretty good English around here.” Then we both laughed. I’d been so proud of myself, and he’d been humouring me out of politeness. There would have been a good laugh at my expense in his village that night.

It wasn’t long before I threw away the phrase book. Nobody in Fiji used the stilted old-fashioned phrases you find in these publications. I eventually paid Jone Raicebi, an educated Fijian in Nabalabala who’d retired from the seminary, to teach me Fijian and lots of fascinating aspects about the culture. He became a handy source of gossip and a valuable sounding board during my 2 years at Uluisaivou.

Settling In

We quickly learned some new words. Cattle of all sizes and sexes are known as Bulemakau a far more descriptive word than cattle beast! And Mongoose which were imported in the late 1800s to kill the Cane Toads, failed miserably with that task, but did clean out the countrie’s native snakes. Mongoose are called Manapussy and it always seemed a bit odd to hear a grown man say he’d just seen a Manapussy.

Houses in tropical areas throughout the Asia Pacific typically have Ghekos, a type of small lizard, in residence. This is to be encouraged because they love eating flies and mosquitoes. These harmless little creatures scamper around the inner walls and ceilings and you can get quite attached to them. If we were quick enough to catch one we’d give it a name and put a tiny dab of nail polish on its back to identify it from its neighbours in other rooms. Other permanent residents were cockroaches which we’d never see in the daytime but they’d emerge out of the drains from the septic tank at night and scuttle around in numbers on the concrete floor in the bathroom. No matter how many we killed we made no impression on their numbers so we learned to co-exist.

Cane toads were a real pest. Situated as we were on a ridge, the lights from our house at night were a beacon to nocturnal insects, and nocturnal insects are a cane toad’s staple diet. In the morning we’d find toads sleeping inside our work boots and in any other hiding place they could find in the vicinity of the house. Their life consisted of eating, defecating, and sleeping as close as possible to their source of food. In desperation I gave Graeme a chaff sack and promised him 20c for every cane toad he caught within the confines of our house. To my amazement he had 85 in a heaving sack on the first day and it was too heavy for him to lift. On the second day there were another 52. He’d made himself some tidy pocket money for our next trip to Suva.

What do you do with 137 cane toads? I drove about 5 kms away and dumped them in the grass on the side of the road.

In the first three days on the job, Tevita and I rode around the widely spaced cattle grazing areas to give me a feel for the layout of the property and the condition of the cattle. I next turned my attention to the office and the farm records.

Kara’s domain

The office was Kara’s domain, she was about 22, she’d had some secretarial training and was an accurate typist but she had attitude and could maintain a no talking haughtiness for hours at a time. She was a good friend to Nicola and Joanna when they were in Fiji on holiday.

I spent hours trawling through the office records trying to make sense of things and I made two discoveries. There was a treasure trove of publications dedicated to tropical agriculture and I burnt the midnight oil soaking up this valuable information.

My second discovery was the lack of material you’d normally find in the office of a sizable farming enterprise. Kara had been doing a good job keeping staff records, the cash float reconciliations, and accounts receivables. So a big tick there.

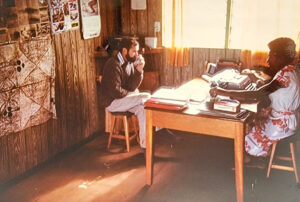

Uluisaivou office

There were copies of the overly optimistic income and expenditure plans underpinning the project when it was signed off by the NZ and Fijian governments. What I couldn’t find was any meaningful information about the actual stock performance figures and what were the plans to redress the woeful 50% calving percentage. In addition I couldn’t get a feel for the death rates because I could find no accurate tallies. Summing up to myself after my first two weeks, I had an uneasy feeling about the feasibility of the cattle ranching dream, but there was an upside.

The Uluisaivou people appeared very supportive of the project. The corporation had provided jobs, roads, river crossings, and better access to health care. A workshop had been set up to maintain the ranch vehicles and machinery, and it earned an income by acting as a repair centre for the numbers of Indian cane farmers who were leasing small plots of native land in the area.

Weighing the Heifers

New Zealand is a world leader in obtaining extremely high production per acre from grazing livestock on superior pastures in a temperate climate. Unfortunately you don’t find a temperate climate, fertile soil, and lush European pasture species in Fiji. The NZ progenitors of the Uluisaivou scheme had paid scant attention to these inconvenient facts I concluded, as I poured over the optimistic budget forecasts I’d found in the office.

Australia had a Cattle establishment aid scheme called Yalavo on the south coast of Viti Levu between Suva and Nadi. I decided to reach out to the manager to ask if I could visit and learn about what they were doing. He agreed but was cool when I introduced myself and had no interest in sharing any salient information, so my long drive there and back was an embarrassing waste of time. I can only assume some bad blood existed between the two institutions. Twelve months later the management at Yalavo changed and Rosie and I became friends with the new couple in charge but by then I’d worked out what needed to be done at Uluisaivou. The immediate solution was a study tour to learn as much as I could about tropical agriculture. I was particularly interested in institutions researching cattle breeds and pasture species that could thrive in the tropics. I put my case to the High Comissioner in Suva and he supported me. I will always be grateful for this because I returned to Saivou with a lot of answers I’ll write about in the next chapter.

More Drama

Before we left Cairn Peak I’d ordered a pair of RM Williams riding boots from Australia but they hadn’t reached NZ before we left, so I asked the new farm manager to forward them to Fiji when they arrived. We got a note to say they were now in Suva so when next in town we paid the duty and released them from Customs before returning to Saivou. With the extra freight and the local taxes they’d turned out to be rather expensive.

The next morning around daybreak, in a fine drizzle, the stockmen and I rode out to a thickly wooded block some distance from the house and commenced a cattle muster. We split up on the top ridge at the start, took a beat each, and drove the mob down hill towards a gathering area near the Nyalegu school. About halfway down I encountered a troublesome Brahman bull. He was tired, thin, and intractable after a long season with his cows. By the time I got him to the bottom of the hill he backed into a thicket of high scrub and was determined to hold his ground. I left him to calm down for a while but eventually it was time to move him on. I spurred my horse after him but he’d had enough. Without warning he spun around and charged.

The next morning around daybreak, in a fine drizzle, the stockmen and I rode out to a thickly wooded block some distance from the house and commenced a cattle muster. We split up on the top ridge at the start, took a beat each, and drove the mob down hill towards a gathering area near the Nyalegu school. About halfway down I encountered a troublesome Brahman bull. He was tired, thin, and intractable after a long season with his cows. By the time I got him to the bottom of the hill he backed into a thicket of high scrub and was determined to hold his ground. I left him to calm down for a while but eventually it was time to move him on. I spurred my horse after him but he’d had enough. Without warning he spun around and charged.

There was a loud crack like a breaking branch, he drove my horse sideways with the momentum of his charge. The horse stumbled but kept his feet, and I looked down at my right leg which was still in the stirrup but flopping from side to side. Both bones were broken through about nine inches above my ankle. Two stock-men lifted me gingerly out of the saddle, laid me on the ground, and when I looked down one of them had his knife out and was cutting off one of my expensive new boots! He couldn’t understand why I was laughing.

Brahman Bull at Uluisaivou

That was the beginning of a very long day and I wasn’t laughing at the end of it. When we arrived at hospital 7 hours later we were told they’d finished operating for the day and we could come back next week. Rosie stormed inside and created such a scene they relented. They performed a rough patch up and put me to bed.

Below is a copy of a letter from the General Manager of the Uluisaivou Corporation to the High Commissioner explaining why I had to return to NZ for professional treatment.

22nd March, 1979.

NZ High Commission

PO Box 1378

Suva

Dear Sir.

Re: KW Fife. Ranch manager.

On Friday 9th March, Mr Fife was mustering cattle with other stockmen. At 9:00 am near the Nyalegu school a Brahman bull was proving difficult to handle, and when Mr Fife attempted to bring him under control with his horse the bull charged and broke his right leg. The local ambulance had already left for Lautoka Hospital so Mr Fife was driven there by Mrs Fife in a short wheelbase Land Cruiser, finally arriving about 4:00 pm. which was after theater time. It was suggested that the leg couldn’t be operated on until Tuesday next, however an attempt was made to set it, but this was unsuccessful. A second attempt was made on Tuesday and a third on Thursday. During Friday night, the plaster broke and the doctor advised on Saturday, that though he was playing golf, if Fife could make arrangements to go to New Zealand he could call him at the Golf Club and the Doctor would write a referral letter to the NZ Hospital.

On the Saturday afternoon 17th. March we found an Air New Zealand plane was due to leave from Nadi to Auckland but it was three hours late. A first class seat was booked for Sunday the 18th. There was no known contact in Auckland so a connection to Invercargill, was taken.

He was delivered to the aircraft at Nadi by ambulance and met by an ambulance at Invercargill. He was, I understand, operated on by fitting plates in his leg on Tuesday and is expected to be released by week ending 31st march.

J A Stone

General Manager

Uluisaivou Corporation

Post Script: My right leg was in plaster from hip to ankle. I was allocated seat 1B, a bulkhead seat in Business class. The problem of getting me into the plane in an airport without an air bridge was solved by opening the front door on the starboard side of the aircraft and hoisting my wheelchair with me in it, up high with a forklift.

I was away for three weeks after the accident and during that time celebrated my 40th birthday in the hospital in NZ among a very small circle of friends. In the meantime Rosie and Graeme were holding the fort at the ranch. Two days after I’d been taken away there was a knock at the door and a senior villager handed Rosie a fillet steak. My bull had been sacrificed to appease “the old people” (this is what the villagers called their ancestors). Two or three young Fijians would have confronted the bull and hamstrung it by slashing the achilles tendons in its hind legs with sharp machetes. This would have brought it to the ground where the machetes would have continued to do their work until the bull was dead. Every skerick of meat would have been shared out among the traditional owners of the land where the accident had happened.This was sad. The meat would have been horribly tough, and I held no grudge against this expensive pedigreed Brahman bull that had been purchased and shipped over from an Australian stud in Queensland.

Under the terms of my employment contract I had to produce a quarterly report for the Foreign Affairs Epartment. Here’s my first one.

ULUISAIVOU CORPORATION

RANCH MANAGERS QUARTERLY REPORT TO THE NEW ZEALAND FOREIGN AFFAIRS DEPARTMENT

JANUARY TO APRIL 1979

We arrived in Suva on 8th January and settled in at the ranch with the maximum of assistance from Mr Matthews of the High Commission and the General Manager, and a minimum of help from the previous Ranch Manager. The refrigerator contained mould and rotting food, the house was filthy and my overlap period and briefing by the ranch manager consisted of a fragmented series of meetings, including some mustering, totaling no more than three days.

On my take over, there were only three saddles for the use of myself and four stockmen, most of the vehicles were in need of urgent repair, the household generator was only putting out about 160 volts so that virtually no electrical appliances would operate, and the maps and farm management records that one would expect to find were scanty or non-existent.

Early in March, I was attacked by a bull while mustering and the resultant broken leg kept me out of action in Lautoka, and then in Invercargill Hospital in NZ for about a month. However, during my time so far on the ranch, I’ve concentrated on.

- Cultivating staff confidence and making as much contact as possible with the villagers.

- Compiling a map of the farmed area and familiarising myself with the office records.

- Assessment of the property and the formulation of my future management plans and recommendations.

Through a series of staff meetings, I have been able to delegate responsibility to the senior staff members and in the next few weeks to the end of June, I hope to concentrate on putting into practice my ideas on grazing management, including the institution of a simple system of rotational grazing. There will also be sugar cane to be planted, harvesting to commence, and 2000 acres to oversow and topdress.

The constraints are, that with the speed of the fencing programme in the last three years, some of the paddocks are only fenced on two or three sides. They aren’t stock proof and effectively the cattle in these areas can roam into village gardens making the corporation responsible for any damage done. Fencing of new areas will need to be curtailed until these issues have been addressed. Mustering and stock work are far from easy given the ground cover and inexperience of some of the stockmen, and the need to push on with the consenting and fencing of new land is also important, as in my opinion we are on the verge of being overstocked.

The cattle were generally in good condition on my take over. The recent consignment of 406 New Zealand cattle also arrived in good condition, but about 10% are too small for their age and should have been culled. This is a rough developing property, not a dairy farm.

My family has fitted into the environment and the community extremely well and with no reservations. We are all enjoying the assignment and experience. The help given by the General Manager to my family while I was incapacitated is gratefully acknowledged.

Ken Fife

Ranch Manager

25/04/1979

Amazing piece of your experiences in the Hills forts of Uluisaivou! Great memories of yester years!

Really love to understand more about the ranch business and.

since I’m a son of Tokaimalo really interested as a Jounalist to get a full story segment of how the Cattle farming started and few other questions I have to personally ask if you don’t mind.

Loloma from Ara na Yadra Land!

Bula Vinaka Meli – Thank you for your interest in my blog. My two years at Uluisaivou were a seminal part of my life. If you’d like to send me your email address I’ll reply personally.