A long time ago, Gronk was sitting by a fire outside his cave. He was aware that a four-legged carnivore had been lurking rather too closely around his camp. On a whim, he threw the bone he had been gnawing. That moment was the dawning of a permanent bond between man and dog.

Eons later, dogs evolved to offer far more than companionship. They can assist man by guarding his property, herding his livestock and protecting domestic animals of all kinds from the predation of other animals.

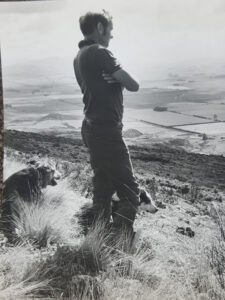

Me, posing with my very first working dog – a Beardy called Tim.

About two weeks ago, Lee and I were out walking, and we came across a young couple proudly pushing a pram. Picture these two thirty somethings. They were dressed stylishly in Melbourne’s winter uniform. Black clothes, and scarves and beanies to keep out the cold. Squatting in the pram staring somewhat imperiously forward, was a small, grey dog.

He had a squashed face, large googly eyes, a wide jowly mouth, small pricked ears and legs too short to propel his overweight body fast enough to keep up with his humans. Even worse, anatomically it would have been impossible for him to carry out a normal social interaction with other dogs.

I’m sure Gronk would have had a thing or two to grunt if he’d been here to witness how prehistoric dogs have evolved!

In 1957 I was employed as a Farm Hand on Te Ruanui Station in Gisborne, New Zealand. I had worked on flat farms previously and this was my first job requiring the daily use of dogs and horses as a condition of my employment. By the time I moved on 12 months later, I knew that working with dogs and horses on hill country would be my future.

In the first couple of months of my new job, I spent a fair amount of time packing out material for a new fence line. I was charged with three pack horses, which when loaded, I would lead up the steep ridges in the picture below, to the site of the new fence line near the top of the hill. This was exhilarating work for a new chum.

Te Ruanui Station

Pack horses have to be strung together. The most sensible horse, the white one in the photo below, would bring up the rear. Her halter was tied to the tail of the second horse who’s halter would be tied to the tail of the first horse. I would lead the first horse, usually the least experienced, by holding his halter from the back of my Skewbald pony called Whiskey. That’s him facing the camera. Three trips a day would typically deliver to the site two strainer posts, 40 fence posts, 200 wooden batons (called droppers in Australia), two coils of wire and the timber required to make a 12-foot gate.

Nowadays, the landscape has changed. Bulldozers have opened up the backcountry, clearing the way for farm bikes and four-wheel drives. As a consequence, reliance on pack horses, saddle horses and even teams of specialist working dogs is fading. In modern times, dogs and fencing material are transported far more efficiently by four-wheel drives. This blog is a wistful tribute to my long-departed four-legged workmates.

Winter on Cairn Peak Station 1965

Nearly sixty years ago, I became the manager of Cairn Peak Station. This was a steep, hill country sheep and cattle property in Southland, New Zealand. When I took over, Cairn Peak was carrying 191 head of cattle and 2,325 sheep. In the ensuing years I transformed from manager to 50% ownership and when I departed 17 years later, the winter carrying capacity had increased to 6,500 sheep and 750 head of cattle. This meant that In the spring and summer months when the new crop of calves and lambs were maturing, there were more than 10,000 sheep and 1,000 head of cattle to look after. And working dogs and horses and four wheel drives were still very much a part of my life.

Nowadays, I find myself living in a street of houses in Melbourne, Australia. The transition from country boy to townie was far from easy, but Australia has treated me well.

Nowadays, I find myself living in a street of houses in Melbourne, Australia. The transition from country boy to townie was far from easy, but Australia has treated me well.

Over the intervening years since leaving NZ, I regularly suffer the same nightmare. Thousands of the farm animals are still out on the hills at Cairn Peak, winter is in full blast, there’s snow on the tussocks, and most of the livestock have become dead-stock due to neglect and starvation. In my dream, these animals are piled up in their hundreds against the top gates where they’ve congregated in desperation to be let back to the life-giving winter pastures below.

Even worse, in my nightmare, my working dogs, abandoned by me, are rotting corpses still chained to their kennels. They too, are dead from starvation.

This, of course, is only a dream, but it happens often – even after all these years, and when it does it’s a relief to wake up. The reality is the dogs all stayed on after I left and were no doubt treated well. Despite this, an irrational guilt has never left me.

A Shepherd and his dog team on New Zealand’s biggest farm, Molesworth Station – 180,000 ha

Working Dog Rules

The overarching rules for dogs in those days were few, but they were sacrosanct.

- Dogs were occasionally patted, congratulated, or rewarded but never fussed over. They had a job to do, and they had to know their place.

- Dogs were never allowed near the house.

- Barking in the dog runs or on the chain was not tolerated, and punishment for doing so was harsh by today’s standards.

- A working day is serious business. The selected dogs are let out and allowed to run around to let off steam while the horses are saddled. The dogs love stock work and will howl to be freed if left behind. Once underway, they have to be kept under control which can be difficult. A stick to wave, a pocket full of pebbles to throw, and loud “Get in behind!” calls maintain order until the muster is underway.

- The biggest sin of all for a dog is “worrying” of other farm animals. That’s code for one or more inexperienced dogs escaping from the kennels, ganging up usually at night, and harassing a neighbour’s livestock. This can result in death or injury to a number of sheep, and can result in the death of the dogs, too if caught by the neighbour. Any farmer who shoots a worrying dog is protected by law in New Zealand, and I suspect this is true in country Australia as well. Interestingly, I’ve never heard of a dog worrying sheep on his master’s property. They know it’s wrong and if they succumb to the delinquent urge, they tend to go further afield.

Those were the main rules for dogs. There was only one convention for humans: NEVER PAT OR ENGAGE IN ANY WAY WITH ANOTHER PERSON’S DOGS!!

A Working Dog’s Life

Hydatids used to be a major problem in Australia and NZ. This is a parasite carried by sheep and also occasionally by cattle. When infected offal from carriers is eaten by dogs, their feces will contain the parasite which in turn can be transmitted to humans due to bad hygiene, or the involuntary breathing in of infested dust in sheep and cattle yards. Hydatids in humans results in parasites in the lungs causing massive cysts which ultimately lead to an unpleasant, wasting, death.

These days, I can’t help shuddering when I see pet dogs lovingly licking their owner’s faces.

The disease has been all but eradicated now, mainly by forbidding the feeding of raw meat and offal to dogs, and strictly observing the proper disposal of animal carcasses Freezing or cooking raw meet and offal destroys the parasite and subsidies were available for the purchase of large freezers to store dog tucker meat. So the daily diet of working dogs was a frozen chunk of raw meet on the bone, fed once a day after work. The dogs thrived on it and there were never worries with bad dental hygiene.

Vet bills in those days were negligible. My dog team numbered 4 to 6 dogs at any one time over the years and apart from medicines and relatively inexpensive veterinary treatments, I don’t recall other major expenditure. There was a dark side, though. Dogs that were uncontrollable, or didn’t have the aptitude for training, were euthanised. And sometimes sadly, this would be done by the farmer with a .303.

All dogs were compulsorily treated against Hydatids at regular periods at the council dog dosing strip. The reluctant dogs would be dosed by the insertion of large pills down their gullet by a council employee. The dogs hated it and if they insisted on regurgitating the pill, the drug was inserted via the anus. It was nothing but a dogs life on dog dosing day!

This is a typical Shepherd’s whistle. They are still widely used today. They can be fashioned from a jam tin lid or bought online for a couple of dollars. A quality dog knows and understands most, if not all of the following whistled commands:

This is a typical Shepherd’s whistle. They are still widely used today. They can be fashioned from a jam tin lid or bought online for a couple of dollars. A quality dog knows and understands most, if not all of the following whistled commands:

Stop – sit – bark – run wide and fast to head off a mob – go left – go right – come here – walk up – shut up – (if barking on a chain!). Not many people can handle the range of all those commands when whistling with two fingers jammed in their mouths.

What Constitutes a Dog Team?

In Australia, farm working dogs tend to be loosely categorized as Herding dogs. The most widely used being Border Collies, Kelpies and Blue Healers or various derivatives. These three breeds assisted by ringers with stock whips and sometimes helicopters in the outback, can handle anything the Australian terrain demands.

In New Zealand, mustering dogs can include the three breeds mentioned above plus two strains that have evolved in NZ . These are the NZ Heading Dog and the NZ Huntaway – larger rangy animals adapted for hill country and the mountainous ranges of the South Island. (source Dr. Clive Dalton. – Farm Working Dogs in NZ.)

Heading Dogs

Their duty is to cast out wide and range behind the livestock to bring them into some sort of control before working them back to the stockman who may be standing by an open gate in a paddock or on a ridge in the high country.

Their duty is to cast out wide and range behind the livestock to bring them into some sort of control before working them back to the stockman who may be standing by an open gate in a paddock or on a ridge in the high country.

Heading dogs can be Border Collies, usually medium haired black and white animals but sometimes also tan and white. Border Collies are bred to show “a lot of eye” which means they control their charges by slinking low to the ground and dominating them with a hypnotic stare until the animals yield and conform to the dog’s will.

NZ Heading Dogs tend to be short haired, larger than border collies and not being dictated to by breed societies, are selected by their intelligence and aptitude, and not by their appearance. Most but not all of these dogs can display “eye” characteristics. The one thing all Heading Dogs have in common is they are silent workers, seldom barking when in control of a mob.

This is an Australian Kelpie (left). Dogs that are game enough to back sheep are treasured, I’ve only ever had one really good backing dog. In my experience most dogs refuse point blank to work on top of a sheep’s back for fear of getting trapped in the middle of the mob.

This is an Australian Kelpie (left). Dogs that are game enough to back sheep are treasured, I’ve only ever had one really good backing dog. In my experience most dogs refuse point blank to work on top of a sheep’s back for fear of getting trapped in the middle of the mob.

Huntaways are the larger of the three dog categories. They usually come in various shades of black and tan, and are short haired with a heavy bark. Their role is to drive a mob away or swing it to take another direction. They are taught to understand the stop, and bark on command whistle whilst facing the animals being mustered. They must also obey the whistled commands for go left and go right.

A typical task would be to send the Huntaway down through a scrubby gully then a little way up the opposite face where some animals could be hiding. You would stop the dog, keep it below the mob and give the whistle to bark. This would drive the sheep or cattle up onto the clear ridge above where the rest of the mob will be congregating before stringing home.

The left and right whistles will guide the dog to the best position to start barking. Most importantly they mustn’t get too close to the sheep or cattle in front of them or they’ll spook and dive headlong into the valleys where they’ll most probably end up being left behind.

Accolades are due to the predominant category, the Handy Dog. Unlike the other two breeds they are not specialists. They come in all shapes and sizes, they must be intelligent and biddable, they must have a basic understanding of the whistled commands and a desire to please. At least one Huntaway, at least one Heading dog, and two or three Handy dogs would commonly form the the basis of a balanced team. Some of the better known strains of Handy dogs used in NZ are Beardies, Blue Healers for working cattle, and the ubiquitous Australian Kelpie.

Accolades are due to the predominant category, the Handy Dog. Unlike the other two breeds they are not specialists. They come in all shapes and sizes, they must be intelligent and biddable, they must have a basic understanding of the whistled commands and a desire to please. At least one Huntaway, at least one Heading dog, and two or three Handy dogs would commonly form the the basis of a balanced team. Some of the better known strains of Handy dogs used in NZ are Beardies, Blue Healers for working cattle, and the ubiquitous Australian Kelpie.

I took the photo below in Iran in 2019. This mixed mob of sheep and goats are being brought back in early evening to be housed to keep them safe from wolves and bears which we were told were a real threat. The mob is much bigger than it looks in the photo. There were three dogs and two shepherds in charge and the white dog leading the mob from the front, was large and confident. One you definitely wouldn’t want to mess with.

I will finish with two anecdotes. In my younger days I acquired a Huntaway called Ben. He was intelligent and capable and quickly asserted his place as top dog. He was also a touch lazy but on most days a star performer. One day in the middle of the muster I cast him out but it was hot and he was tired and he hid in some bushes while his charges were ducking off the wrong way. We wasted a precious half hour trying to regroup from the resulting problem, and I called him back and gave him a whack with my stick. Before I could think of delivering a repeat stroke I found my wrist very tightly clamped in his jaws. We looked into each others eyes and instantly understood each other.

Never before or since has a dog attacked me, nor until then did I have any perception of the strength of a dog’s bight. My skin wasn’t broken and the encounter did neither Ben nor me any harm but I was taught by a dog that day, that the use of a stick when a dog’s been working hard, is not the most intelligent way to gain loyalty.

I once had a handy dog called Sue. On one occasion when she was 8 or 9 years old and very close to whelping there was some mustering to be done and I took off with a couple of dogs and a Land Rover, knowing Sue was too far advanced in her pregnancy to be participating. Ten minutes later I saw a very puffed dog in the rear vision mirror about half a mile behind me, doing her best to catch up. I reversed, lifted her onto the tray and continued out to Black Gully to start our muster. She was lying down on the back when I cast out a Handy Dog to drive the mob out of the scrub below.

The next thing I heard was excited barking and Sue was barreling down hill in full pursuit of the other dog. She was also too engrossed in the chase to take any notice of my call to come to heel. Suddenly she stopped, squatted down for a few seconds then continued on to join the chase. When this happened twice more I realised this incredible dog was trying to whelp her pups and muster cattle at the same time. I should have left her tied up at home!

I waited for quite a long time but she didn’t come back. Eventually I gathered the mob together and set off for the cattle yards and home. At day break next morning, still no sign of Sue. I went back to the top of Black Gully ridge but she was nowhere to be seen, so I called out and was rewarded by a short answering bark from close by. On investigation I went to where it came from and found her under a scrubby bush curled around a litter of 7 healthy pups.

This remarkable animal had located her pups in the very widely spaced places in the scrub where she’d dropped them, and carried them one by one, an incredibly long distance, back to where she knew I’d come to look for her.

Modern Times.

These days a revolution has taken place for our four legged friends. In the towns and cities the business of breeding pet dogs and keeping them healthy is a multi million dollar industry. It isn’t practical to have large hair shedding dogs as house pets in suburbia. As a result, strains of jaunty smaller dogs are being bred. Most are good natured, non hair shedding, fit enough to live a normal doggie life and able to go for a long walk with their human. These animals give immense joy to millions of people. It can be truthfully said that their contribution to the mental health of some people is incalculable.

Unfortunately, there’s a down side to doggie well being caused by some humans being more needy than their dogs. It’s all too common to see dogs being treated like babies even when in their advanced years. They have their toys and beds and warm coats and rain coats. Their owners call themselves mummy and daddy and it’s perfectly normal to see them being wheeled in prams, or carried like handbags. I watch these developments with awe. What is being done to the dignity and sense of well-being of the more intelligent of these poor animals?

I’ve wanted to write my love letter to working dogs for a long time now, and thanks to Covid 19 and forced lockdowns, the job is finally done. I hope there will be many more years yet for the task of mustering the hills and high country to be performed principally by musterers with dogs. But at some time in the future, could expediency dictate their replacement by stockmen on motor bikes with drones? I hope not.